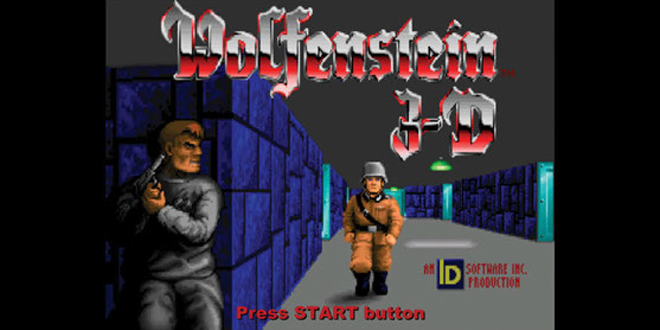

Before there was Doom, there was Wolfenstein 3D. The 5th of May 1992 saw the release of Wolfenstein 3D, developed by the now legendary studio id software. While the game was the third entry to the forgotten franchise, its shift to fast-paced first person shooter action was revolutionary for the time. Not only was Wolfenstein one of the first video games to truly embrace brutal, bloody violence, it proved so successful that it spawned an entire genre.

30 years on, Wolfenstein is fondly remembered as the grandfather of 3D shooters – a genre that has dominated the industry for decades, particularly since the meteoric rise of Call of Duty. It’s a legacy worth celebrating, particularly as the 3D shooter genre continues to adapt and evolve in new and exciting ways – with the recent rise of the battle royale genre standing out as an exceptional example of innovation in the space.

So as we pay tribute to a watermark moment in gaming history, it’s only right that we sit down with John Romero, co-founder of id software and widely regarded as one of the founding fathers of the shooter genre. Lucky for us, Romero is due to speak at the upcoming Develop:Brighton, taking place from July 12-14th and organised by Tandem Events.

Romero’s talk, a postmortem on Wolfenstein 3D, will chronicle the journey that led id software’s founders to create gaming history. We’ll save you the spoilers, as I’m sure you’re as keen as we are to attend Romero’s session, taking place on Thursday, the 14th of July. That said though, we’re certainly not going to turn down the experience to pick Romero’s brain as he looks back on the game’s 30-year legacy.

A 30 YEAR LEGACY

“In the beginning, [Wolfenstein 3D] was influential because nobody had played a game like that before,” says Romero. “And our choice of IP using Castle Wolfenstein was pretty unique. There was a category of world of World War Two games, mostly in strategy on computers back then. This was nothing like that.

“We didn’t even think of it as a World War Two game really, we just loved the original Wolfenstein. It didn’t, we felt, have heavy World War Two overtones because it was so limited in its graphics and everything. It had a great story, and the original game was definitely inspired by World War Two movies. But when we made it, we weren’t thinking so much about that. We were thinking mainly just about run and gun.”

Now, in the context of how games have evolved since 1992, Wolfenstein is remembered primarily as a first person shooter. But when discussing its legacy, its place in the now-forgotten maze genre shouldn’t be overlooked either. “Wolfenstein was like, the most glorified maze game,” Romero laughs. “Even though it was heralding a new way of playing games at high speed with that 3D perspective, the walls were all 90 degree corners and had fixed ceilings. Which was very similar to everything that had come before – from RPGs like Ultima, Might and Magic, Bard’s Tale, that kind of stuff.”

The primary difference, of course, being the focus on run and gun – maintaining the player’s momentum as they tear their way through the level. Encouraging exploration, sure, but always making sure that they keep moving, with id cutting any element of the game that they felt disrupted this high-speed flow – setting the groundwork for decades of shooters to come, including but not limited to id’s followup title, Doom.

“After Doom, the explosion of shooters that came out really showed a broad range of content and subject matter. Sci-fi, westerns, you name it, even in IP with Dark Forces (Star Wars), Jedi Knight and that kind of stuff. It really spread out after that point. Wolfenstein was really not the main focus, like it had been for that year and a half until Doom came out. “But Wolfenstein, to me, feels like it’s so niche. Battlefield and Call of Duty are totally different things, with different timelines and everything. Wolfenstein is Wolfenstein, it stays there. I feel that it is its own thing, separate from the other World War Two games.”

BOOMER SHOOTERS

It’s perhaps that drive to ‘be its own thing’ that has inspired the recent resurrection of the ‘boomer shooter’ — titles that harken back to the classic shooters of the 90s, many of which were pioneered by Romero himself. The revived genre has not only seen the return of both the Wolfenstein and Doom franchises, but has even inspired a host of indie games looking to replicate that 90’s shooter feel.

It’s perhaps not a huge surprise – Not only is the 30 year nostalgia cycle likely playing a part, but games like Wolfenstein 3D and Doom fundamentally defined what shooter games could be for a whole generation of players. And while the genre has moved in new directions over the years, you can hardly blame players for wanting a return to basics. Especially when you consider that this resurrection has taken place during an interesting time for shooters. While in many ways the genre has been pushed to new heights with the advent of battle royale titles, this rise has also been matched with a growing linearity – at least in terms of single player campaigns.

“To me, the resurrection of these retro shooters feels like people want to get back to that 90 aesthetic. The way you play those games is not the way that you play today’s shooters. Call of Duty introduced this objective based, pushing through a level, all very scripted… That’s taking away from the freedom people have to just try and survive in a level. Go ahead! See if you can get past this point, see if you can survive – and then open worlds really magnify what you can do in that area.

“I kind of go more towards the open world game, because I like to explore and that aspect of shooters was kind of getting removed when you have games like Call of Duty and Battlefield. Games that have these giant teams that cost a lot of money, and the less QA you have to do the cheaper it is to make the game, so you start walling people off and it starts to feel linear. And that linearising of shooters, is one of the reasons why people want to get back to the freedom that they used to have.” Beyond their linearity, another issue many people have with modern shooters is how they’ve largely abandoned old staples of the genre, in favour of focusing on shooting galleries. This, combined with the trend over the last decade or so of deproritising single player experiences, has caused the genre to often feel somewhat homogeneous, at least to a casual observer. “There used to be fun puzzles to solve!” says Romero. “They’re not really puzzles now, they’re just about overcoming an arena of characters, and then pushing on to the next arena.

“You know, some people love that. Some people love the movie aspect of Call of Duty and Battlefield – plus the multiplayer is really, really fun. They basically have the best multiplayer code that exists, kind of like how World of Warcraft probably has the best for an MMO that’s ever existed, Call of Duty is that for shooters. “But I think people just want more variety, they want that fun puzzly exploration stuff. It’s why, I think, that Sigil (Romero’s 2019 Doom episode) did so well. Because it goes back to the design that made these games really fun – it’s serving that retro market.

“I think people are looking for more variety, because they feel like there’s some sameness and maybe some limitations to what they can do. You know, when you play Warzone, you’re not exploring. When you play any of these games in the battle royale space, you do need to learn the levels really well, so you can expect where people are going to drop or places they’re going to go. And that’s great, it gives you mastery of the level. But it is like ‘oh, we’re playing the same level over and over again.’ I remember I used to be able to go through a story, going through all these different exciting spaces, and just exploring and learning everything about it instead of being shuffled towards the exit.”

That isn’t to say Romero is at all dismissive about battle royale titles. Games like Fortnite and Warzone have become two of the biggest names in the industry for good reason. After all, I myself have been ensnared in a Warzone-centred group chat for the better part of a year now. But the genre is perhaps more of a useful next step, rather than a radical evolution of the genre.

“I think it’s good for creators to try new things,” says Romero. “Even if they’re not going to work out, some of that could be a hint to what might work out. If you’re exploring how to expand the genre, if there’s not any clear big ideas then you just go forward and incrementalise on what you think might be the next step of something, versus a revolutionary thing. Battle royale is huge, but the funny thing is it could have been in the original Doom. If you had a big enough level with 100 people playing, you could have battle royale in Doom. The rules are not a genre, they’re just the rules. And those rules can be in any game.”

“The reason battle royale really worked, I think, is because when you play a free-for-all kind of game, you’re dead pretty quickly. Those games are only for hardcore people, but the battle royales are for everybody, because you can decide where you want to land — and it can be away from everyone else, so you can have some fun running around and picking things up. And maybe you’ll kill somebody, so at least feel like you got some gameplay, and when you’re killed at least you learnt something and had fun. So I think the battle royale formula actually helps people get into deathmatch shooters. That [battle royale] ruleset could lead to something new, it could lead to someone making something that points in the direction of what all shooters should have. I wouldn’t mind having battle royale in pretty much all shooters, so long as that’s not the only thing that shooter is.”

THE FUTURE OF FPS

Not that Romero ever expects shooters to become any one thing. As much as Wolfenstein 3D once defined what a shooter could be, Romero is keen to stress that it should never just be that. While Call of Duty so often dominates the conversation around shooters today, the genre is far more diverse than it’s often given credit for. While new trends like battle royale may attract a lot of attention, they’re a part of a wider expansion of the genre rather than seeking to redefine it entirely.

“There are so many differences in shooters nowadays that I don’t think that Call of Duty is the North Star for the whole genre. It’s a kind of shooter in the same way that Overwatch and DOOM Eternal are both kinds of shooters. None of them are like, ‘this is what a shooter is.’ They’re one of the things that a shooter could be. “I don’t think that any one of them is pointing to the future, they’re all kind of incrementally moving forward in their subgenres, their niches, and any of that stuff could become the beacon for a new rule set that everybody jumps on top of, in the way that PUBG was. I think it’s great that it’s not just one thing, and it has a lot of different playstyles and stories people can point to. These different games can have these cool features that can become the standard, like the way Half-Life 2 had the Gravity Gun and physics puzzles – but you know, things people could actually take forward!”

Of course, the shooter genre isn’t the only thing to have changed in 30 years. Looking back on the development of Wolfenstein 3D is like gazing into a time capsule from a lost civilization. For instance: the Wolfenstein IP, one of the most recognisable franchises in gaming history, was acquired by the Wolfenstein 3D team for just $5,000 in 1992. Just comparing that to the enormous figures involved in gaming acquisitions today is enough to make your head spin. Additionally, during development publisher FormGen approached id software with concerns over its violence and shocking content. The team, in what is perhaps my favourite decision in gaming history, responded by making the game even more violent and shocking.

EDITH’S GOT A GUN

While this was unquestionably the right move in hindsight, it’s still somewhat strange to look back on an era where Wolfenstein 3D could have been considered too violent and shocking, a game that could almost be considered wholesome family-friendly fun today were it not for all the portraits of Hitler. “I don’t think it’s an issue anymore, but back in the day it was a shock. It’s just like heavy metal, D&D, and comic books. If it’s a cultural thing that kids jump into, then everyone thinks it’s bad. And then it just becomes normalised, and you wait for the next big thing that you’re gonna get upset about.”

“I think games are past that point. You have really great quality games like The Last of Us and Uncharted, there’s so many good games with extremely well told stories. The rise of the narrative game is just amazing to watch. What Remains of Edith Finch is a high watermark for games like that. That’s what shooters are looking for, an Edith Finch that can really show where we can go, something exciting and new and not like what we’ve been doing for 30 years. Like the way Minecraft came out and showed a whole new way of making games, that you can create and have gameplay at the same time. How do we do that without making it look like we’re copying it?”

Back to that (excellent) anecdote about FormGen’s concerns about the game’s violence, though. While we admire the punk rock attitude of rejecting your publisher’s input, is this a freedom that’s afforded to developers today, as budgets (particularly in the triple-A space) spiral out of control? After all, id only had the creative freedom that they did because they were funding the project themselves, which hardly seems like an option for many developers today. At least, so we thought.

“That still happens every day, all over the place,” says Romero. “There’s so many indies. Maybe you’re doing it independently, you’re not being paid to do it, it’s your own time and your own idea. You can make a shooter in Unreal 5 way easier than you could have in the past. So you’re going to see more indie shooters that look incredible, and they’re doing what they want. “I’ve been playing shooters that people have made exactly how they want. It’s massively violent, it’s super fast, it’s exactly what they wanted to do. And those things are coming out, and if they’re adopted by players during early access, then it shows that they’re on the right track and they can hire more people and up the production value, because they’re getting some income.”

“The early access stuff is great for indies to validate their new design ideas, and to get the money to actually make them come out in a really good state. Subnautica did an amazing job going from that early access to a full release, with so much support from the community. People wanted to play that game because it was really unique, and it’s a kind of thing that happens in shooters now. Get it on Steam, get it on Early Access, try out new ideas. And if it doesn’t do really well, at least they made something and they’re going to do it better next time.” I think it’s fair to say that even three decades on, Romero has retained his optimism and excitement for the future of shooters, and the future of games in general. While we can’t exactly predict what the shooter landscape will look like over the next 30 years, we can be sure there’s plenty of exciting new ideas coming to the genre.

Which, for a staff writer burnt out on a genre so often overloaded with grim military shooters, is a breath of fresh air. “The fact that you might not see it happening doesn’t mean people aren’t trying,” says Romero. “More games are shut down than are ever published, and that’s just a pile of death. A pile of dead things, and the people who were making them stacking them on top and moving forward. It’s non-stop, it happens every day and there’s so many of them. “You could say that the genre is saturated but when you have people with new ideas coming into it, people who have belief that the genre still has tonnes of room to grow, then there’s somewhere to go in here. That’s why the genre keeps moving forward.”

John Romero will be addressing the Develop:Brighton conference on Thursday 14th July.

MCV/DEVELOP News, events, research and jobs from the games industry

MCV/DEVELOP News, events, research and jobs from the games industry